Microclimate Factors in Your Garden: Why They’re Important

INSIDE: Garden microclimate factors.

Do you struggle to choose plants that will thrive in your garden?

Sun, shade, heat, wind, slope, precipitation, and soil type all work together to create microclimates in your yard.

As a beginning gardener, one of my biggest frustrations was getting things to grow in parts of my yard that were too dry, shady, hot, or windy.

I decided to learn more about the different microclimates in my garden to choose plants that would thrive.

There are five simple steps you’ll need to follow to understand your garden’s microclimate.

Keep reading to find out what they are.

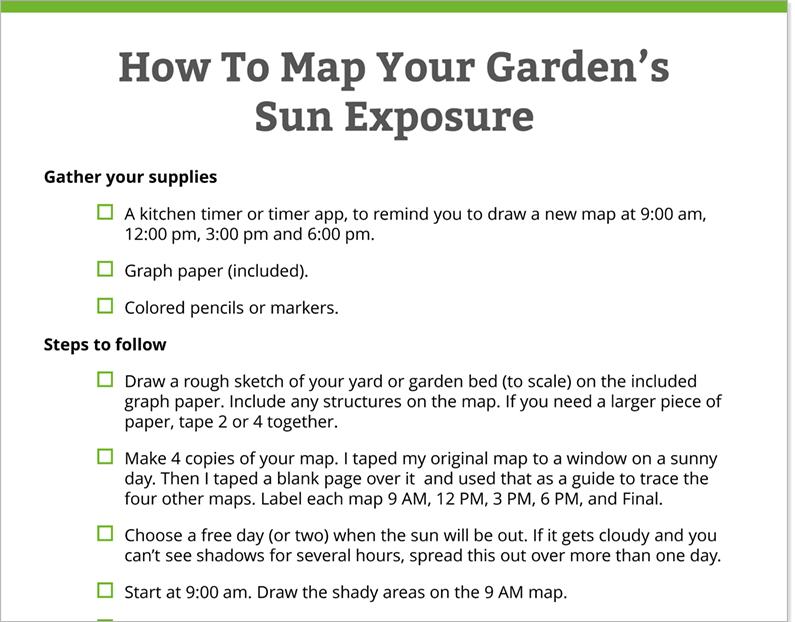

But first, have you signed up for my free sun mapping checklist? It’ll help you figure out how much sun your garden gets. Grab it for free here.

Understand your garden’s microclimates in five steps:

Heads up: I’ll earn a small commission if you buy something after clicking a link in this post. I only link to products I’d recommend to my best friend.

1. Know the length of your growing season

The length of your growing season is the number of frost-free days you have. Knowing this helps you make better choices about what vegetables and flowers to grow.

Some growing seasons are so short that growing tomatoes to a successful harvest is difficult without a greenhouse and late-blooming perennials can be killed by frost.

New gardeners can get caught up in the warmth of spring days and plant tender, warm-season vegetables too early. But that won’t happen to you, because you’ll know your last frost date.

- The days between the last frost and first frost are your “growing season” for warm-season crops.

- To calculate the length of your growing season, you need to find the first and last frost dates for your area.

- You’ll find these dates using your zip code or the city or town where you live.

What to know about frost dates

- First and last frost dates are guidelines.

- They give you an idea of when it will be safe to plant warm-season crops in the spring, and when to harvest certain crops in the fall.

- You still have to watch the weather forecasts since Mother Nature is unpredictable. Watch for freeze warnings so you can protect any plants that might not do well with a late or early frost.

Related: DIY Sunlight Calculator. It’s the easy way to map your garden’s sun exposure.

How to find your first and last frost dates

Finding the first and last frost dates for your area can be tricky. You’ll get slightly different dates depending on where you look.

When I searched for my first and last frost dates I got these answers:

- From The Farmer’s Almanac: First: May 9 Last: Sep 29.

- From Dave’s Garden: I got a table showing how likely it is to be a certain temperature on certain dates. It could be confusing for some new gardeners. So, I continued searching.

- From the CO cooperative extension site, I found a “climate summary” for my area in a fact sheet for master gardeners. The dates listed here match up well with the information I got from The Farmer’s Almanac. And I trust the Colorado extension office.

Take action:

- Either call your local extension office or search their website to get your first and last frost dates.

- Get a second opinion from The Farmer’s Almanac site.

- If these sources don’t match up, you can try searching your local paper’s online archives or call a local nursery.

- Don’t rely on sites that list your first and last frost dates based on your hardiness zone. We’ll dive into gardening zones in a minute, but your hardiness zone only relates to your minimum average winter temperatures, not frost dates.

- When you have your first and last frost dates note them in your gardening journal.

- Calculate the length of your growing season, and enter it into your journal.

Related: Download a free garden design workbook.

Now that you have your last and first frost dates, what should you do?

When you’re getting close to those dates, pay attention to potential frost/freeze warnings in the weather forecast.

Cover up plants that could be damaged when there’s a frost warning.

The covers must be big enough to reach the ground. They work by trapping heat radiating from the ground.

Remove the covers the next morning when the frost danger has passed.

Cover plants with:

- row-cover fabric rated for frost protection

- old bedsheets

- cardboard boxes or empty pots for small plants

Pro tip: NEVER use plastic to protect plants! Plastic transmits cold to plant leaves and will cause them to freeze.

Now that you know how long your growing season is, how do you use this information?

- For vegetables, it’s important to know how long your season is because all vegetable varieties have an estimated “days to maturity” number. You’ll find this on the seed packet or online.

- Warm-season vegetables need to fit within your growing season.

- If your season is short, you won’t be able to grow some varieties or types of vegetables. You won’t have the number of warm days required for them to mature.

Gardeners who live in warmer climates think my growing season is short. But it’s still long enough that I can grow any warm-season vegetable I want. I steer clear of ones with long maturity times.

For example, I’d never grow a Moon and Stars melon. It takes 100 days to mature. My growing season is longer than 100 days. But melons need a lot of heat to reach maturity, so I don’t have enough warm days (and nights) where I live for this variety.

2. What are growing zones and how to find yours

A gardening zone is a geographic area in which certain plants can grow, based on climatic conditions. Cold, heat, and rainfall define gardening zones.

There are three gardening zone numbers you should know.

- Hardiness zone

- Heat zone

- Sunset climate zone (if you live in the Western U.S.)

How to find your hardiness zone

Knowing your hardiness zone (frequently called just “gardening zone” or “planting zone”) helps you determine if a perennial plant, shrub, or tree is likely to live through your winter. Your hardiness zone is only one factor that affects winter survival rates, but it’s a good place to start.

Hardiness zones are “based on the average annual minimum winter temperature. Gardeners use that information to “determine which plants are most likely to thrive at a location.” – USDA.

Go to the USDA plant hardiness map to find your zone. If you live outside the U.S., look at this post about hardiness zones of the world.

The USDA updates the map occasionally. The map has recently been reclassified due to global warming. I used to be in zone 5b; now I’m in 6a.

The zones are ranked from coldest (1) to warmest (13).

The zones are also sub-divided into “a” and “b,” with “a” being colder than “b.”

Take action: Find your hardiness zone. Note it in your garden journal.

How does knowing your hardiness zone help you?

- You’ll learn what plants can survive your winter.

- You can avoid plants that aren’t hardy in your zone.

- Any zone that is higher than yours is warmer than yours in the winter. While you’re still a newbie stay away from plants labeled for those zones unless you’re growing them as annuals.

Let’s look at a real-life hardiness zone example

Let’s say you live in zone 6a.

You could theoretically grow plants that are hardy in zones 1-6a.

But plants listed as zone 6b and above are too tender for your area.

Your winter temperatures are likely to kill plants rated as 6b and above.

- Could you grow a plant that’s hardy in zones 3-8? Yes.

- How about one that’s rated 6b-11? That’s tricky. You’re at the end of the range, so a plant like this might be a risk.

- What about a plant that’s hardy in zones 7-9? No.

Avoid plants too tender for your zone, unless you’re prepared to dig up the plant and overwinter it inside.

- Digging up plants to overwinter is common practice with tender bulbs like gladiolas.

- Avoiding tender plants isn’t a hard and fast rule, but as a new gardener stick to it.

- When you get more experienced, you can experiment and try things that are on the edge of your zone. How far you can venture out of your zone depends on your yard’s microclimates.

How to find the hardiness zones for a particular plant

- Always look at plant tags and catalog descriptions.

- Trees, shrubs, and perennials typically have a gardening zone on their label.

- Many plants sold as annuals state no zone on the tag because it’s assumed that they won’t survive your winter.

- You can also find hardiness zone information online. Search for the plant name and “hardiness” or “zone.”

Find your heat zone

Excessive heat can be just as devastating to some plants as too much cold is for tender plants.

But heat damage in plants may not be as obvious to a new gardener. It looks like a slow decline.

Plants may appear stunted, flower buds may die, or leaves may appear yellow, whitish, or fall off completely.

The American Horticultural Society developed a heat zone rating system. It helps you decide which plants will tolerate the heat where you live.

“Heat days” are the average number of days each year that an area has temperatures over 86 degrees Fahrenheit. At that temperature, heat-sensitive plants start showing signs of damage from heat.

There are 12 zones.

- They range from 1 to 12.

- Zone 1 gets less than one heat day per year.

- And zone 12 has over 210 heat days.

Finding heat zone information for plants can be difficult. If it’s on the tag, it’s listed after the hardiness zones. For example, a plant listed as 5-10, 11-1 is hardy in zones 5 through 10 and can tolerate the heat levels in zones 11 through 1.

The American Horticultural Society published a reference book, AHS Great Plant Guide, which lists over 3,000 plants and their heat zone (and hardiness zone) ratings. It’s my go-to reference for heat tolerance.

Take action: When you find your heat zone, write it down in your garden journal. If you live in an area with a high heat zone rating, purchase the Great Plant Guide. It’ll help you make better plant choices.

Find your Sunset climate zone

If you live outside the Western U.S., you can skip this step.

Sunset magazine has divided the U.S. into 45 Climate Zones and takes a nuanced approach. They based the zones on latitude, elevation, ocean influence, continental air influence, mountains, hills, valleys, and microclimates.

Identifying your Sunset climate zone if you live outside the Western U.S. can be difficult. I located a climate zone map of the entire U.S. But I only found descriptions of the zones in Western states.

Take action: If you live in the western U.S., find your Sunset climate zone and write it in your garden journal. Consider buying Sunset’s guide to Western plants. It’s heavily West-coast focused, but can be invaluable for gardeners who live in those areas.

Knowing your gardening zones isn’t enough.

It’s a good starting point, but to understand what plants will do well in your garden, learn as much as you can about your yard’s microclimates. We’ll talk about those below.

And a big factor that contributes to microclimates is the sun.

3. Map out the sun exposure in your garden

How much sun and shade a garden will get is one of the most important microclimate factors to plan for.

Here’s how to measure sunlight in your garden.

Take time to figure out how many hours of sun your garden gets by sun mapping your garden.

You’ll get the best sun exposure data if you do this in the summer on a day that’s predicted to be sunny.

Some clouds won’t be a huge problem but don’t do this on an overcast day with no shadows.

4. Definitions of sun exposure in gardens

- Full sun is six or more hours of direct sun per day.

- Partial sun is 4 to 6 hours of direct sun per day.

- Partial shade is often used interchangeably with partial sun.

- Full shade is less than 3 hours of direct sunlight per day.

Plant tags, gardening reference books, and online descriptions will tell you how much sun a plant needs to thrive.

For more details, see: What is Full Sun, Partial Sun, and Part Shade?

5. Identify the microclimates in your yard

It’s not enough to understand your overall climate and sun exposure. Microclimates can dictate what plants will survive in what parts of your yard.

Back to table of contents.

What causes microclimates?

- Low spots are colder (especially overnight) and wetter.

- High spots are warmer and drier.

- Slopes affect your microclimates. In the northern hemisphere, southern slopes are sunnier, warmer and drier, and northern slopes are shadier, cooler, and wetter.

- In the northern hemisphere, buildings, fences, and walls cast shade on the northern side and reflect heat on the southern side.

- The east side of a yard gets gentle, morning sun.

- The west side of a yard gets the stronger afternoon sun.

- Windy spots can desiccate certain plants, and put wind loads on trees.

- The south and west sides of buildings, large rocks, rock walls and retaining walls collect heat during the day and radiate it out at night.

- Urban areas are heat sinks. They’re warmer than rural areas due to buildings and pavement.

- A neighborhood with lots of mature landscaping has lower summertime temperatures.

- Neighborhoods and cities with a lot of hardscaping (little vegetation, and lots of hard surfaces like pavement or gravel mulch) will be hotter and may be drier in the summer.

- Tall, mature trees produce dry, shady areas under them, but they also cool the air.

- Soil type also affects microclimates. Sandy soils dry out quickly, and clay soils hold water.

- Winter snow cover (or lack of it) affects how well plants will survive winter. Deep snow can insulate the ground and help plants survive.

- Lack of snow can be a problem, especially in dry areas where the ground freezes. It can freeze-dry plant roots. And it can cause plants to heave due to freeze/thaw cycles that snow cover would lessen.

- Plants favored by local wildlife may die if they’re too tasty.

Spend time figuring out where your yard’s microclimates are, and what causes them. It may take a while to dial it in and figure out the microclimates in your yard. The above list is a good place to start.

How to manage the microclimates in your yard

Planting the right plant in the right place is a good first step, but there are things you can do to change some microclimate situations.

- Windbreaks will help reduce wind. Tall hedges are the best windbreaks.

- Planting shade trees will help to cool an area.

- Diverting excessive water rainwater will help with drainage.

- Reducing some of your hardscaping (rock mulch, concrete, etc.) and replacing it with plants will reduce heat buildup.

Pro tip:

If a plant doesn’t do well in your yard, don’t give up. Note it in your garden journal. Then think about whether you put it in the best possible microclimate.

If you think a plant could do better somewhere else, try moving it or plant a replacement in a better spot.

I have a “three strikes, and you’re out” policy with plants. If I’ve tried a plant three times and it doesn’t thrive in my yard, I don’t grow it.

In my yard, I’ve struggled to establish groundcover plants on a dry south-facing slope. It gets blasted by the sun in the summer, has little to no snow cover in the winter, and is raked by the wind all year long. Oh yeah, and the plants need to be deer resistant!

I haven’t found the perfect ground cover for this area, but knowing what challenges the plants in this harsh microclimate will face helps me narrow down my choices significantly. Eventually, I’ll find the perfect plant for this spot.

Take action: Make a list of all the microclimates in your yard, and note the challenges (hot, windy, etc.). Note this in your garden journal.

Now that you’ve learned about your garden’s climate, we can get to one of my favorite parts, planning your garden.

Chapter 3 is all about how to get started with garden planning.

Leave a comment and let me know what microclimates you’ve struggled with in your yard. And how you’ve tried to solve the problem. And I’d love to hear how your sun mapping project turned out!

How can I make my garden warmer?

Creating garden beds on the south side of walls and structures (north in the southern hemisphere) or building raised beds are great ways to create cozy microclimates in your garden.

How can I reduce wind in my garden?

Plant a hedge to help to soften the wind and lessen its power. To reduce wind damage use secure ties to fasten climbing plants to sturdy supports. And regularly prune plants to avoid any damage to weak, leggy growth.

How does soil affect microclimate?

The composition of soil can have a huge effect on an area’s microclimate because it influences water retention or evaporation. Take clay soils, for instance – they hold onto more water than sandy soils. This soil moisture can affect the humidity and temperature in the air. Plus, the amount of bare soil can have an effect on the surrounding temperature, too – bare soils tend to reflect more of the sun’s rays, making the air above it warmer.

Read the rest of the chapters in this Gardening 101 series:

- Garden Fundamentals

- Microclimate Factors (you’re here)

- Designing a Garden for Beginners

- Prepare Your Soil The Right Way

- Choose the Right Mulch for Your Garden

- Growing a Low Maintenance Garden

Download a free sun mapping checklist

Snag this free sun calculator checklist so you can know exactly how much sun your garden gets.